UK’S CONFORMITY ASSESSMENT AND ACCREDITATION:

KEY ISSUES FOR THE UK-EU RESET

BRIEFING PAPER 86 – JULY 2025

PETER HOLMES AND SAHANA SURAJ[1]

Download Briefing Paper 86

KEY POINTS

- Duplicative testing against similar regulations have created additional costs for UK-based manufacturers when producing goods for sale on domestic markets and for exports to EU markets.

- Attempts to create an independent UK conformity system have led to practical difficulties and increased reliance on EU infrastructure, undermining one of the original goals of Brexit.

- A Mutual Recognition Agreement (MRA) on Conformity Assessment Bodies on a sectoral basis would allow manufacturers and sellers to use results produced by third-party laboratories and other testing facilities from accredited bodies in their own country to demonstrate compliance with the regulatory requirements of the partner country.

- A totally comprehensive MRA of this nature would also need to include mutual recognition of accreditation systems to build trust while ensuring the quality of products in alignment with regulations and relevant standards.

- Securing an MRA on Conformity Assessment with the EU would primarily but not only benefit UK manufacturers and sellers. The EU has less economic motivation to recognise UK CABs. To improve its chances of negotiating a comprehensive deal of this nature, the UK must consider offering deeper regulatory cooperation and legal commitments, while targeting reductions in trade frictions in sectors of higher strategic importance to the EU. If this is not achievable in the medium term, the UK must identify product areas where EU trading partners would also benefit.

INTRODUCTION

Recent calls from several UK exporters and industry associations for a UK-EU agreement on Mutual Recognition of Conformity Assessment[2] highlight an important aspect of trade facilitation challenges. The negotiating agenda for the UK-EU “Reset” did not include any reference to this. In the last few weeks, we saw a hint of such an agreement in the UK-US deal which approaches the issue of regulatory misalignment through national treatment of conformity assessment bodies and accreditation agencies. On the other hand, there have been hints that the EU might proceed[3] . This briefing paper explores why a “mutual recognition” of conformity assessment bodies and principles of accreditation for goods is so important for the UK, but also hard to achieve. It discusses the challenges that must be addressed to overcome the potential EU reticence in the process.

THE STRUCTURE OF THE QUALITY INFRASTRUCTURE SYSTEM

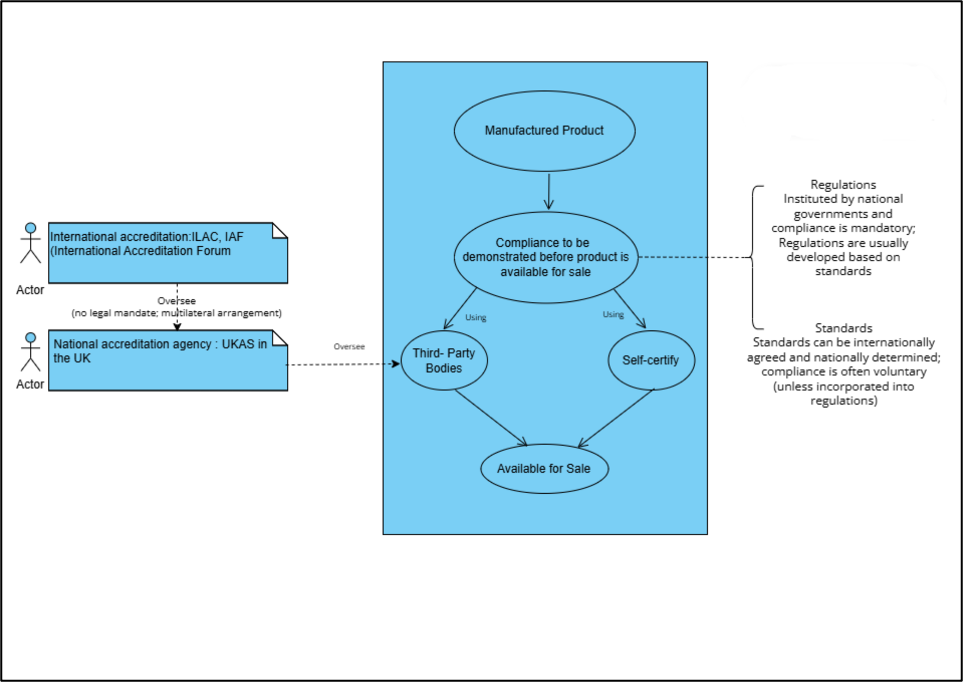

Conformity assessment procedures can play a pivotal role in linking product standards and regulations with trade opportunities. Using these processes, consumer safety and legal compliance is ensured by testing and certifying products against requirements outlined in regulations. Manufacturers can prove conformity to regulatory or commercial requirements either through self-declaration, using in-house labs or third-party organisations. However, which of these routes is used depends on what is specified in the relevant regulation or commercial requirements applicable to the product. In cases that require a third-party assessment of conformity assessment procedures, manufacturers and sellers must use the services of Conformity Assessment Bodies (CABs) that evaluate products, processes and facilities against the regulatory requirements[4].

The Standards and Quality Infrastructure system operates in a system of checks and balances where all stakeholders within the system are thoroughly vetted as depicted in Figure 1. While CABs are used to test and/or certify products and inspect installations, accreditation procedures are needed to validate the CABs and in-house test labs. Using accredited testing labs and other conformity organisations, manufacturers can be assured of the competence and impartiality of testing, certification and other evaluation services. Accreditation bodies operate at a national level and accredit CABs using internationally determined and nationally agreed standards. Additionally, national accreditation bodies, designated by the government in each state[5], are connected to the international conformity assessment framework through their memberships in the International Laboratory Accreditation Cooperation (ILAC), International Accreditation Forum (IAF) and European co-operation for Accreditation (EA).

Mutual recognition of the results of conformity assessment delivered by CABs through Mutual Recognition Agreements (MRAs) allows manufacturers and sellers in partner countries to have their products and procedures evaluated by CABs in their home countries. They can then use these results when trading with partner countries.

Fig 1: Structure of the Conformity assessment ecosystem for goods

THE STATE OF PLAY IN THE UK

While the UK was a part of the European Union, trade was facilitated by uniform product regulations across the EU. There was also mutual recognition of test procedures, results and access to CABs. Hence a UK accredited and designated CAB could be used to certify products for the whole EU market and vice versa.

Upon leaving the EU, conformity assessment tests and CABs are no longer mutually recognised between the UK and EU for regulatory compliance purposes. As a result, sellers exporting to EU markets and selling to domestic markets may need to undergo two tests of conformity: one against British regulations using UK CABs and one against EU regulations using EU-based CABs, even if the rules are identical. It is for the UK to accredit UK-based CABs for the sale of products in the UK, and for the EU to do so for EU-based CABs (including subsidiaries of UK entities and those issuing CE marks recognised by the UK). In the case of the fireworks industry, recently, BAM (the notified body[6] for pyrotechnics in Germany) has been approved as a body that can offer regulatory conformity assessment for fireworks for UK rules. There was a 2-year accreditation phase where BAM’s compliance to operate in the UK as a notified body had to be verified by UKAS in accordance with ISO/IEC 17065[7]. With the accreditation of BAM, it became the sole CAB in the UK to assess fireworks or their production processes to UK regulations in the UK – with no other bodies being approved. Meanwhile the UK government has also indefinitely extended the recognition of the CE mark for pyrotechnic products within the UK. This decision allows the use of CE marks issued by EU-based notified bodies accredited by member state bodies. This allows EU-based producers to sell in the UK market based on the CE mark and effectively sidelines the UK’s own UKCA conformity assessment system [8].

Before September 2024, the UK had decided that for construction products CE marks would not be recognised in the UK after June 2025. This was meant to incentivise the use of the UKCA mark which would be issued by UK CABs that were accredited and designated in the UK. The EU recently consolidated and upgraded its Construction Products Regulation offering an enhanced role for CE marking.[9] Under the updated Construction Products Regulation, CE marks can be used to demonstrate technical compliance and environmental impact to ensure products meet sustainability requirements. Within the UK 57% of total imports of construction materials originate from EU countries and 60.2% of exports of construction materials are to EU destinations[10]. Given this trade dependency, it became clear that there was likely to be a shortage of building materials due to the lack of domestic productive capacity, the unwillingness of EU firms to pay for UKCA marks and the resulting decline in the UK certification capability in the area. Hence in September 2024, it was judged necessary to recognise the CE mark for an indefinite period[11].

The above instances solved the problem of lack of imports, but not the problems of securing certification for domestic production and the ability of domestic producers to cater to the needs of the domestic market. Extending the recognition of the CE mark still means that goods manufactured and intended for sale within the UK, which require third-party certification, must be certified by an EU-based notified body to obtain the CE mark. This discourages domestic production and challenges government initiatives aimed at encouraging home manufacturing. However, it solves the problem of double testing costs. Additionally, the increased reliance on EU infrastructure to support imports into the UK highlights the limitations of the belief that Brexit would allow the UK to develop its own regulatory frameworks.

ACCREDITATION AND CONFORMITY ASSESSMENT IN THE RE-SET

The possibility of an agreement to reduce barriers caused by Conformity Assessment issues was discussed before the Resent negotiations[12]. However, this was not mentioned in the Reset Agenda document.[13] Unfortunately for the UK, the EU is, for several reasons, unwilling to consider such a proposal at this point[14]. To put it at its bluntest, the EU side considers the requirement for dual testing by UK firms to be a minor inconvenience for EU importers. The UK has had to recognise CE marks, but the EU sees little benefit in acknowledging UK certification.

The sectoral developments noted above remind us that dynamic alignment with EU regulations is not sufficient to ease trade facilitation challenges. It requires binding institutional actions and recognition of conformity assessment bodies and procedures across the border. A first step towards enabling UK firms to secure market access to the EU without needing product certification from an EU-based and accredited body could involve establishing a Mutual Recognition Agreement (MRA) on conformity assessment. This agreement could recognise a limited number of accredited CABs in the UK and EU in specific sectors, negotiated government to government.

The UK has the strongest interest in securing a MRA on CABs for a broader number of sectors, given that the EU is its largest trading partner. The recent call for such an agreement has also received backing from some important EU business associations. However, the EU Commission has repeated its opposition to a cross-cutting MRA on conformity assessments – though the UK is actually the EU’s second largest external market for goods.[15]

As a long-term objective, the conclusion of a comprehensive MRA on CABs would need to be underpinned by agreement on other elements of the conformity assessment system- particularly accreditation, above all if it were to be broadened. The Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) between the EU and the UK (Article 93 on conformity assessment) does spell out an agreement in principle on the common use of accreditation, but it does not provide for mutual recognition. United Kingdom Accreditation Services (UKAS) is a member of the European co-operation for Accreditation (EA), which allows for the acceptance of equivalence of accreditation systems and reliability of conformity assessment results produced by accredited bodies. However, within this ecosystem, MRAs generally only apply to a specified list of mutually recognised CABs. A broader agreement on accreditation should ideally apply to all CABs unless there is a specific reason to exclude any. The goal must be to ensure that CABs accredited by one partner are recognised as designated bodies by authorities of the other partner. This approach would allow for a broader recognition of sectors covered under a potential MRA. A similar solution was proposed by the UK in the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA)[16] An MRA for CABs covering a broad range of sectors and regulations would likely require some legally binding guarantees of alignment on the rules governing conformity assessments between the UK and the EU, as well as close regulatory cooperation. The EU has long resisted “cherry picking” solutions, but the current improved atmosphere (and the recent EU-Swiss deal) might make this approach possible.

This leads us to the issue of relations with the US. The recent agreement between the US and the UK [17]contains an agreement to negotiate on national treatment for CABs under the UK-US “Economic Prosperity Deal”. This does not mean harmonising standards or unconditionally accepting US assessment certificates. It appears that UKAS would need to accredit US testing facilities as competent to assess products made in the US as being in conformity with UK rules, provided that the testing bodies satisfy UK requirements. In principle, an agreement to offer national treatment would allow US CABs to be considered equivalent in the UK, even though the US accreditation regime is less tightly regulated than those of the UK or EU. There is a risk that the US might take a very hard line on insisting on the equivalence of US CABs, even though the US accreditation regime is less strictly regulated than the UK or EU systems, making National Treatment very similar to Mutual Recognition.

Although the distinction between mutual recognition and national treatment may hold little significance for businesses, the type of agreement chosen can have important implications for regulators. Any agreement to offer national treatment for accreditation principles and testing procedures, must avoid compromising British adherence to international standards. It would also require UKAS to apply strict controls on what US testing bodies would be able to operate in the UK or to certify compliance of US exports with UK rules.

The UK must handle any negotiations with great care. Failing to do so could create fears and the reality of UK standards (in the general sense) may be effectively watered down. And it might further weaken the British position to negotiate a sectoral MRA for CABs with the EU. This is because such an agreement would directly stand in opposition to the EU’s iron-clad regulatory structure. In this context, the EU has not ruled out offering Trump some kind of mutual recognition or national treatment deal: the ‘realpolitik’ of trade negotiations kicks in here. The US is a significantly bigger market than the UK and does not recognise EU certification, giving it leverage.

CONCLUSION

Despite the challenges, as Garcia Bercero and Grabbe argue[18], a comprehensive agreement on mutual recognition of conformity assessment that embraces the accreditation system is a goal that should still be pursued. It is important to note that, the narrower the scope of an MRA on CABs, the greater the chance of pressures for border checks to ensure that non-compliant goods do not slip through the net. Our case studies indicate that the UK’s experience at ‘go- it- alone’ regulation has delivered little. Although tough conditions may be necessary for an agreement on accreditation, it would be worthwhile to explore a way to achieve a broad MRA on CABs. In a forthcoming paper, we intend to explore how an agreement of this nature has been implemented in the past and shed light on lessons for the future.

FOOTNOTES

[1] We are extremely grateful to Richard Collin and colleagues at UKAS and the UKTPO for comments and advice, but the authors are solely responsible for the opinions expressed and any errors.

[2] UK & EU industry calls for mutual recognition agreement to boost growth — UK Trade and Business Commission

[3] The case for such an arrangement is made for example in https://ecipe.org/blog/call-on-the-eu-us-ttc/

[4] It is important to note that Conformity Assessment Bodies (CABs) provide services that allow manufacturers and sellers to meet market requirements and/or legal obligations. Through this piece of work, we are interested in investigating the legal requirement for the usage of CABs as outlined in product regulations and the trade facilitation challenges in accessing and utilization of these services.

[5] The US has a distinctive regime.

[6] Notified bodies, in the EU legal taxonomy, refer to a category of CABs that are employed by manufacturers and sellers to meet regulatory requirements, accredited by a member state accreditation body and then notified by a member state government. In the UK, “Approved Bodies” are comparable to the function of Notified Bodies.

[7] BAM – News – BAM becomes official body for pyrotechnics testing in the United Kingdom

[8] We are grateful to Rob Bettinson of UKAS for background information on this. Any errors are ours.

[9] Thanks to Jacob Oberg for drawing our attention to this.

[10] https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/building-materials-and-components-statistics-february-2024

[11] See https://www.gov.uk/guidance/construction-products-regulation-in-great-britain

[12] See Ignacio Garcia Bercero https://www.bruegel.org/policy-brief/trade-policy-framework-european-union-united-kingdom-reset; along with Heather Grabbe he does believe it may be put on the agenda later: https://www.bruegel.org/first-glance/eu-uk-reset-first-big-step-right-direction

[13] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/ukeu-summit-key-documentation/uk-eu-summit-joint-statement-html

[14] Brussels rebuffs UK bid to prise open access to EU single market

[15] This data is based on 2023 figures published by the European Commission available on: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=International_trade_in_goods_by_partner#:~:text=The%20following%20section%20presents%20information,the%20United%20Kingdom%20and%20Switzerland.

[16] Trade economists refer to “positive list agreements” which only cover named sectors, vs “negative list agreements” which cover all sectors except those specifically excluded.

[17] Text of the agreement can be found here: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/us-uk-economic-prosperity-deal-epd

[18] Garcia Berco and Grabbe https://www.bruegel.org/first-glance/eu-uk-reset-first-big-step-right-direction