The rise of China in the US backyard amid Trump Tariffs

Written by: Valeria Terrones Rodriguez, Manuel Tong Koecklin

The uncertainty caused by the trade policy actions undertaken by the Trump administration poses a serious challenge to the world, but particularly to regions that historically relied on the United States both as a commercial and political ally, such as Latin America.

The Trump 2.0 regime has levied a baseline 10% tariff on most Latin American countries[1], including those that have a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with the US, such as Chile (2003), Peru (2009), Colombia (2012), and Panama (2012). The uncertainty surrounding the permanence of such measure (and the potential for further protectionist actions) will encourage these countries to seek and consolidate more secure trade links with like-minded partners, with more predictable trade policies. Such a shift has already been happening. The US has gradually been losing its relevance as the main trading partner for some Latin American countries, particularly those in the south, with one key actor playing a central part in this story: China.

China’s penetration in the South American market over this century has been taking place at different levels. Regarding trade, China has Free Trade Agreements in force with Pacific countries like Chile (2006), Peru (2010) and more recently with Ecuador (May 2024). Trade and investment links with South America may strengthen even more given China’s candidacy to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) of which Chile and Peru are already members. On the Atlantic side, China’s bonds with Brazil through BRICS are also growing.

China’s regional objectives have moved a step forward, by undertaking large investments in port and logistic infrastructures as part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. This is currently visible in two different ways. Firstly, in November 2024, Peru and China inaugurated the first stage of a megaport located in the town of Chancay (75 km from the capital Lima), mostly controlled by Cosco Shipping, a company owned by the Chinese government, meant to be fully operational by 2032. This new infrastructure, apart from heavily contributing to the Peruvian economy, is expected to facilitate South American trade with China and the Asia-Pacific region, with products shipped directly from Peru, instead of passing through Mexico or the US. Secondly, earlier in 2024, China and Brazil inaugurated a new maritime trade route, operated by the same state-owned company, linking several Brazilian ports with the Chinese port of Tianjin, and expected to significantly reduce the travelling time of containers between both countries from 54 to 40 days.

Despite concerns regarding the dominance of China in South America and in the global logistics network (which could be used for political coercion and even for national security purposes) reactions from the US have been minimal. For example, during his four years as president, Joe Biden only visited the region once, for the APEC annual meeting in Lima followed by the G20 summit in Rio de Janeiro, right at the end of his presidency. Conversely, Xi Jinping, since becoming President of China, has visited South America five times. Recently, there was only one reaction by the US: a threat to levy a 60% tariff on any product using Chinese port infrastructure in the region, made just four days after Trump’s inauguration. Overall, the impression is that, apart from hot issues like immigration and drug trafficking, the US has neglected South America in numerous aspects. This perception has been reinforced with the cut of US foreign assistance programmes and an immigration policy based on massive deportations.

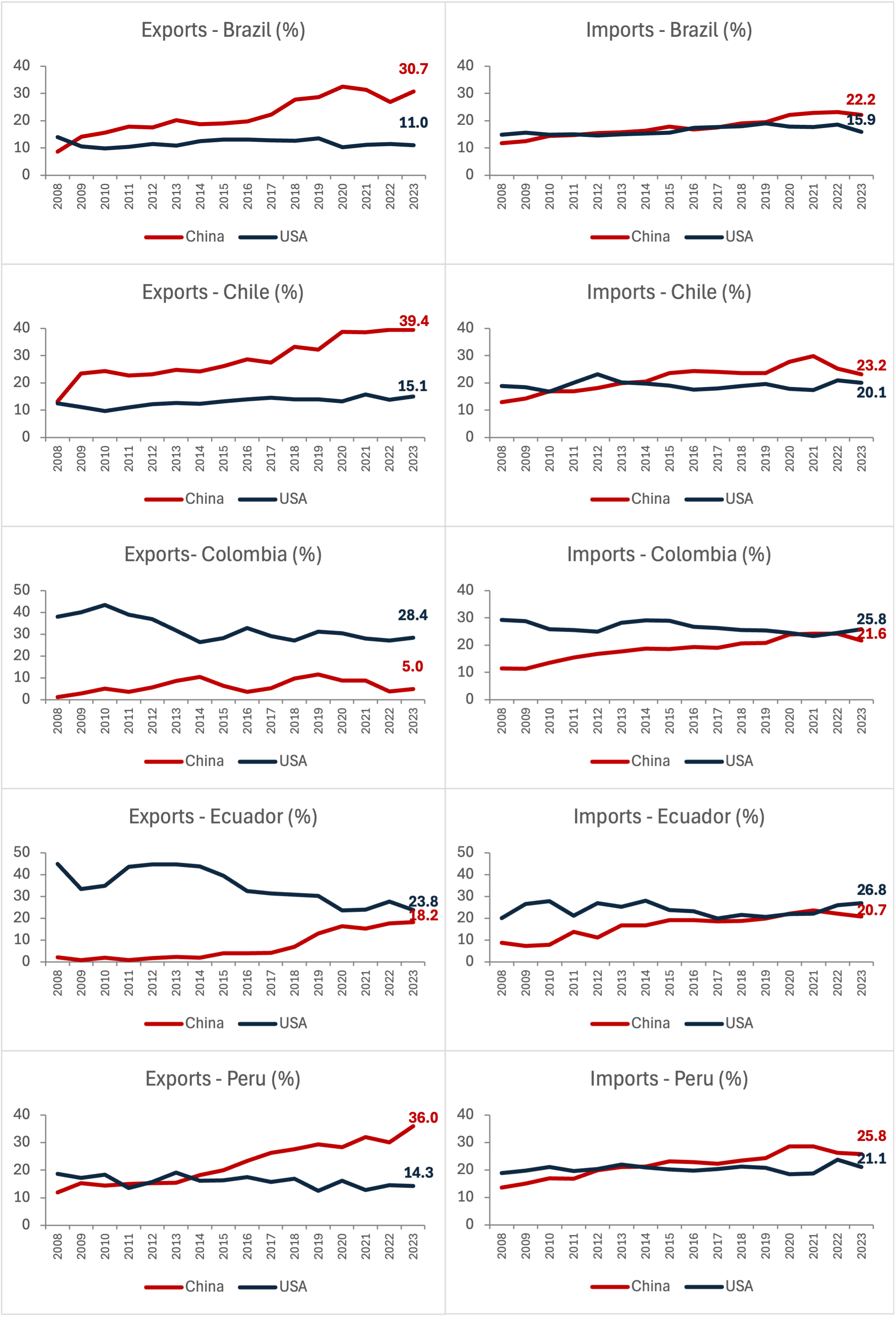

Using trade data from UN COMTRADE[2], we have tracked the relevance of China and the US in the exports and imports of five South American countries: Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru[3]. Figure 1 is informative in many ways.

Figure 1

China and USA Trade Shares in South American Markets, 2008-2023

Source: UN COMTRADE (WITS World Bank). Own calculation.

Firstly, it shows that these five countries depend highly on China and the US as an export destination and import supplier. This places them in a vulnerable position. Indeed, between 33.4% and 55.5% of their exports in 2023 went to those markets, whereas shares range from 38.1% to 47.5% for imports. Secondly, Figure 1 shows the existence of heterogeneity within the region. While Colombia and Ecuador still had the US as their main trading partner between 2008 and 2023, to a greater extent on the export side, for countries like Brazil, Chile and Peru, China has gained increasing relevance. The case of Peru is illustrative because since 2014 China has displaced the US as the main export destination, leading to 36% of Peruvian exports going to China in 2023, compared to 14% sold to the US. That displacement is found to have occurred earlier in Brazil and Chile. The latter registers export shares for China of nearly 40% since 2020. In the case of Ecuador, despite the larger export figures for the US, China’s role is growing at an intense pace.

On the import side, we see a more homogeneous pattern across countries: China’s share of imports has been steadily increasing, surpassing the US as the primary source of imports around the mid-2010s in Brazil, Chile and Peru. With regards to Colombia and Ecuador, China’s share became equal to that of the US around 2021.

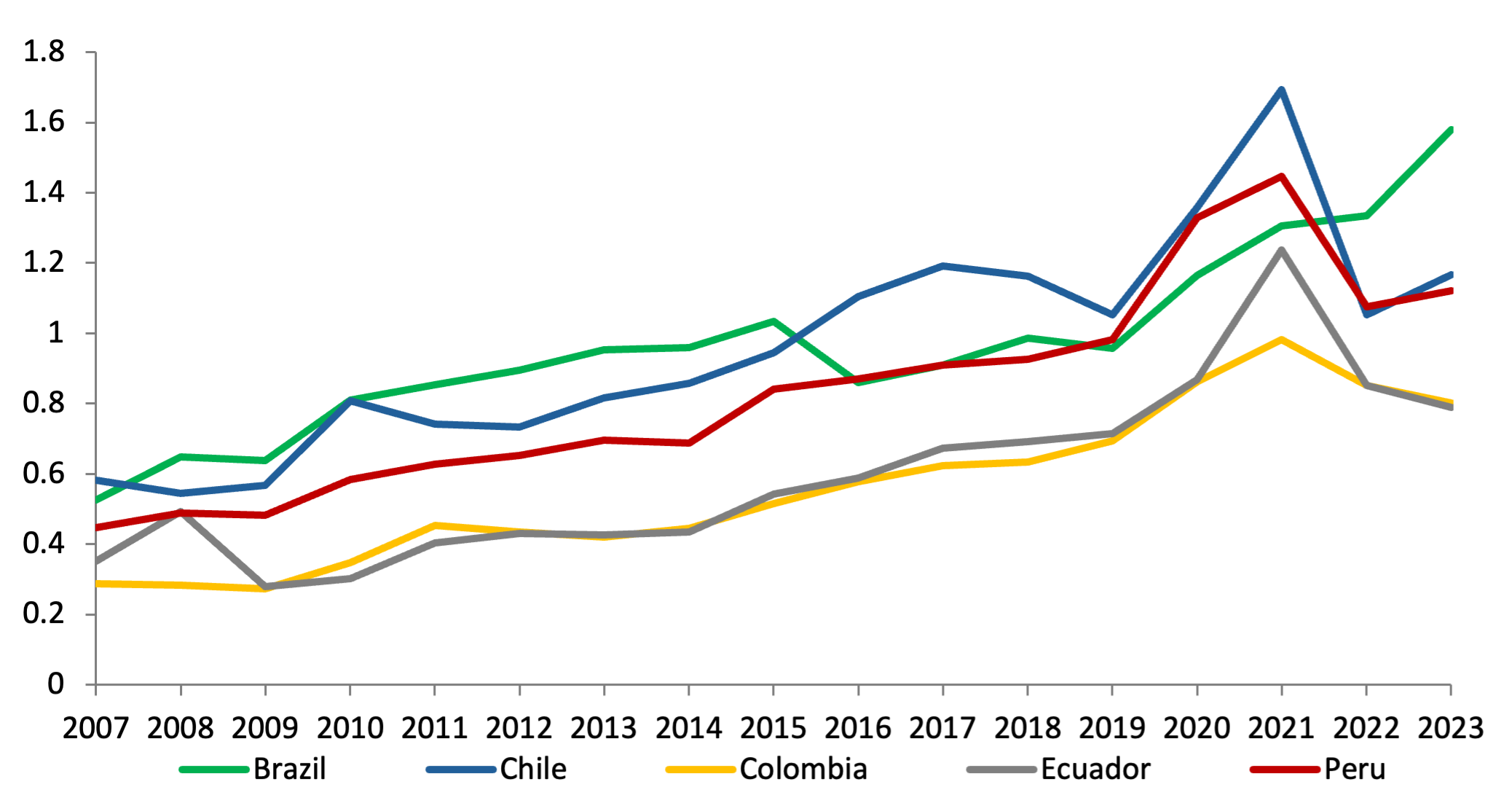

However, US figures have remained flat throughout the period of analysis. Those aggregate numbers should not concern the US if both countries sold different products to the region, i.e., if they did not compete with each other. In Figure 2, we compute a Relative Export Competitive Pressure Index (RECPI), to measure the degree of competition that the US faces from China in each South American market.[4] Results clearly show an increasing index level over time for the five countries. This suggests that, when accounting for trade size, China has become a more serious competitor for the US, even in Colombia and Ecuador, by exporting a similar product portfolio.

Figure 2

USA’s RECPI of Chinese Exports to South American Markets

Note: The Relative Export Competitive Pressure Index (RECPI) measures the degree of competition that the US faces from China in each South American market.

Source: UN COMTRADE (WITS World Bank). Own calculation

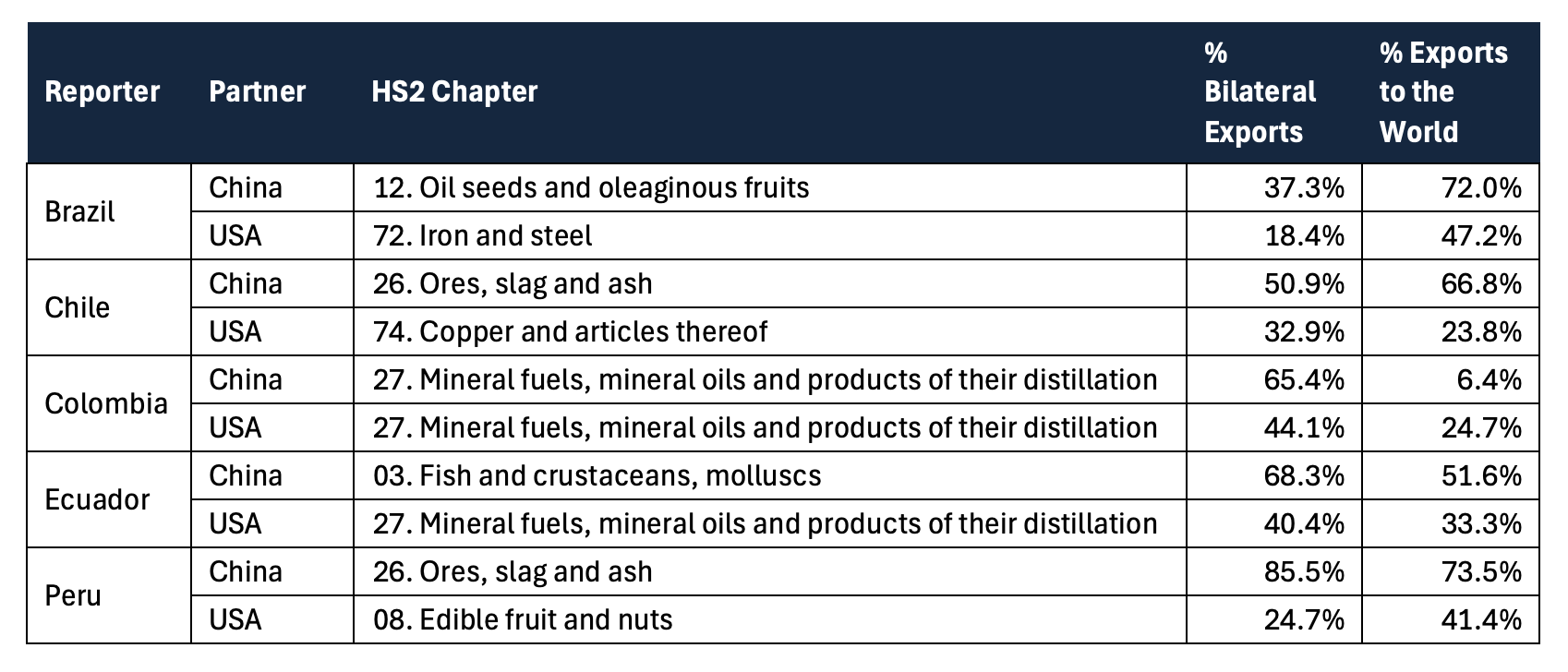

A concern for South American countries amid this trade war is how heavily their trade of certain products or industries depend on China and the US. In Table 1, we list each country’s main HS2 chapters traded with China and the US in 2023, capturing their relevance, both relative to bilateral and world trade. Let us take, for instance, Brazilian exports to China of HS chapter 12, mainly composed of soybeans. These account for 37.3% of sales to China, but that trade flow also represents 72% of total HS 12 Brazilian exports to the world. That is, Brazil largely relies on China as a destination for its oil seeds and oleaginous fruits. Similar conclusions can be drawn for HS 26 exports (ores, slag and ash) from Chile and Peru. For Peru, over 80% of its exports to China correspond to that chapter (mainly iron and zinc ores and concentrates), which also make up over 70% of sales of those commodities to the world.

Table 1

Main HS2 Chapters Trade with China and USA – 2023

a. Exports

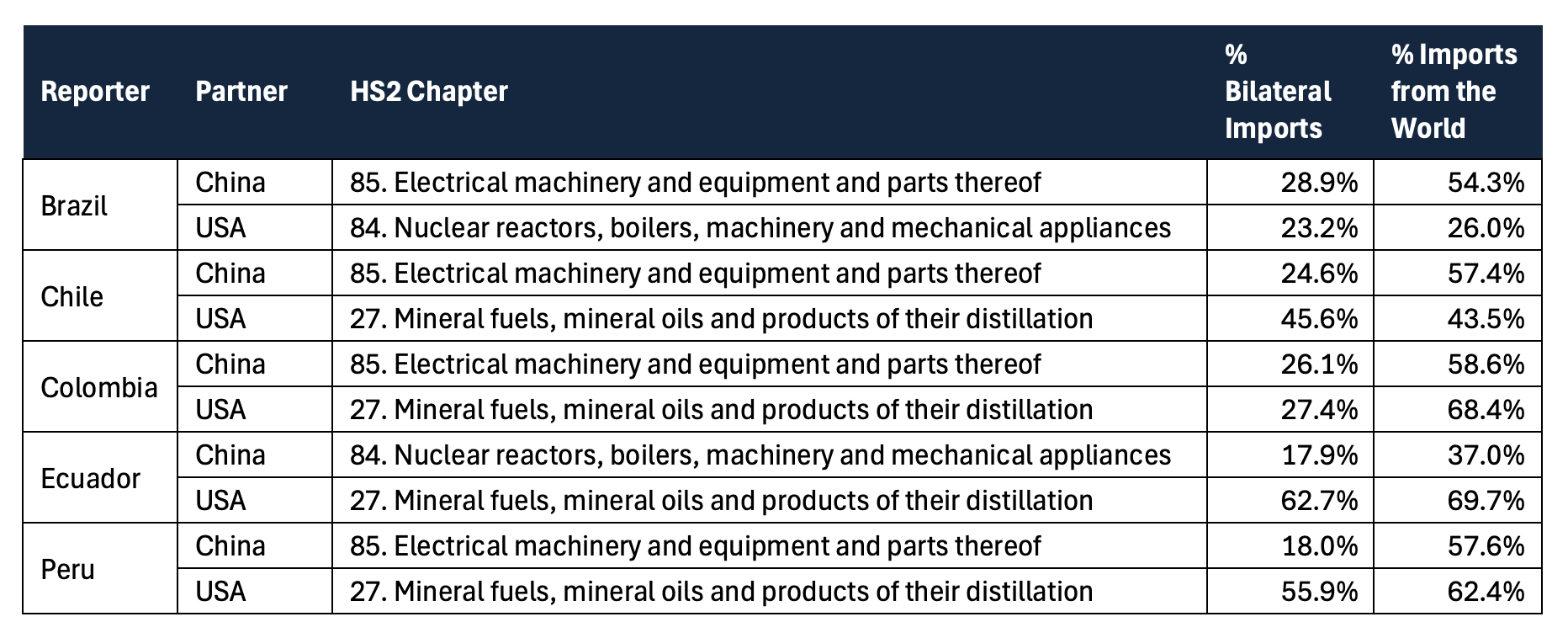

b. Imports

Source: UN COMTRADE (WITS World Bank). Own calculation

In 2023, both China and the US constitute highly important South American sources of electrical machinery, nuclear reactors and mineral fuels – HS chapters, 85, 84 and 27, respectively. In many cases, those bilateral imports account for more than 50% of their world purchases. That is the case of mineral fuels (HS chapter 27) from the US, which make up over 60% of total imports of Colombia, Ecuador and Peru. That heavy reliance could be used by the US to put pressure on South America to politically align against China. As a resource to restrain such pressure, we could think about the US reliance on some countries for the supply of critical minerals. In 2023, the whole South American region accounted for between 20% and 30% of US imports of minerals like tin, copper, ores, slag and ash (HS chapters, 80, 74 and 26, respectively).[5] That would require a determined desire of regional coordination to make those figures work as a negotiation tool.

This scenario of large dependence on two trading partners involved in a trade war leaves South American countries in a complicated position, and China looks better positioned to take advantage of this scenario. Indeed, China has an ambitious policy of investment and consolidation in the world trade logistic network. As the trade war with the US evolves, China may use its position to divert those products blocked in the US market to alternative destinations, including South America. On the other hand, the permanence of a 10% tariff on all products might represent a sizeable cost to some South American producers. As a result, these producers may look to China as an alternative, more accessible destination, given the existing FTAs. By using that new Chinese-owned infrastructure, they would further increase their reliance on China[6].

In this challenging context, South American countries have the chance to undertake initiatives that strengthen their economic and trade position. First, they should diversify their trade dependencies to reduce overreliance on the US and China. This can be done by reinforcing commercial ties with other key partners, such as the European Union and the United Kingdom, and through enhanced intra-regional trade. Second, South America holds a strategic advantage in the global transition toward renewable energy and digital technologies, due to its vast reserves of critical minerals. With significant deposits of lithium and copper—key components in renewable technologies and lithium-ion batteries used in smartphones, laptops and electric vehicles—South America is poised to become an increasingly relevant player in green industrial value chains. To fully capitalise on this potential, governments should enforce existing regulatory frameworks, foster business incentives, and adopt forward-looking industrial policies that encourage value-added production.

Additionally, fostering competition and transparency in emerging maritime routes, along with investing in trade-related infrastructure, will be crucial for unlocking long-term trade advantages and strengthening the region’s role in global supply chains.

[1] The US government excluded Mexico and imposed 15% of tariffs to Venezuela and 18% to Nicaragua.

[2] Available on the World Bank’s World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS).

[3] Other South American countries have been excluded, since regional trade between them is more predominant.

[4] The Relative Export Competition Pressure Index (RECPI) is an indicator designed to measure the average degree of competition a country faces from another in a third market, by considering both the structure and level of competing countries’ trade. In this blog, the more similar product portfolio to the US China has in a South American country (expressed by similar product export shares in the third market) and the larger exports China sells to that country, the larger the RECPI, meaning that China constitutes a serious competitor to the US in that market.

[5] Chile accounted for 16.1% of US copper imports in 2023. Peru and Bolivia made up around 25% of US tin imports. Finally, Peru and Brazil represented around 16% of US imports of ores, slag and ash.

[6] That increasing reliance and influence of China has already raised concerns in South American countries and some actions have been taken. In Peru, for instance, the competition regulatory authority has found potential abuse of monopolistic power by China in the Peruvian port service market, leading to propose the application of price regulations. In Brazil and Chile, to prevent the proliferation of cheap online purchases from China, have scrapped tax exemptions on low-value foreign purchases by individuals.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.